- Dae-Wook Kim

- PhD in Sociology (Seoul National University); Associate Professor, School of Law, Shandong University (Weihai)

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

- DW Kim ‘The role of the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in ensuring disabilityinclusive responses to climate change in Africa’ (2024) 12 African Disability Rights Yearbook 3-19

- https://doi.org/10.29053/adry.v12i1.5528

- Download article in PDF

Summary

This paper investigates the often-neglected topic of disability-inclusive climate action, focusing on the recommendations from the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities for African countries. The author’s analysis reveals a consistent emphasis by the Committee on climate change in its Concluding Observations, particularly in relation to adaptive capacity for climate-related disasters. Key recommendations typically encompass emergency and disaster risk reduction strategies, the provision of information in accessible formats, and the establishment of engagement channels with disability representative organisations. However, the Committee’s climate change discussions fail to adequately address the unique attributes of the African region and its individual countries, leaving several crucial issues unresolved. These issues encompass the need for improved international cooperation and a focus on disability sub-groups with climate-related concerns. The paper advocates for the Committee to intensify its efforts to address disability-inclusive responses to climate change, including general recommendations for the inclusion and recognition of the diversity of persons with disabilities and a strategy for international collaboration on climate change.

Climate change is a global menace, yet its detrimental effects are not evenly distributed and largely hinge on geographical factors. Ironically, it is the developing countries, which contribute minimally to climate change, that endure the brunt of its impacts. Recognising this inequity, the ParisAgreement - the cornerstone of international climate change governance since 2015 - emphasises the imperative to understand the unique ne eds and circumstances of developing nations, especially those most vulnerable to the harmful repercussions of climate change. 1

Africa is expected to be severely impacted by climate change due to its close ties with the climate system, the complexity and unpredictability of its weather patterns, and the substantial degree of climate change anticipated.2 As the driest continent in the world, Africa faces significant challenges related to water stress caused by climate change, potentially affecting up to 700 million people. Over the past 230 years, the number of scorching days in Africa has increased sevenfold.3 Surface temperatures in arid areas of Africa are likely to rise more rapidly than the global average. Additionally, heavy precipitation events and flooding will become more frequent and intense in Africa.4 However, the most crucial factor is Africa’s limited capacity to adapt to these changes. This is why African nations consistently confront challenges associated with disasters and escalating climate change risks. 5

Climate change disproportionately impacts members of marginalised communities.6 The Paris Agreement acknowledges that parties should respect, promote, and consider their respective obligations related to the rights of indigenous peoples, local communities, migrants, children, persons with disabilities, women, and those in vulnerable situations when addressing climate change.7 Persons with disabilities are particularly susceptible to the detrimental impacts of climate change, primarily due to constraints in resources and socio-economic hurdles.8 Climate change not only intensifies pre-existing challenges but also introduces new difficulties that are unique to those living with disabilities.9 For example, persons with albinism, who are more commonly found in sub-Saharan Africa, may face an increased risk of skin cancer as a result of climate change.10 Likewise, persons with disabilities such as multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injuries, whose conditions are influenced by temperature sensitivity or thermoregulation, can also experience adverse effects due to high ambient temperatures. 11

Various international frameworks highlight the importance of incorporating persons with disabilities into climate action strategies. For example, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 stresses that ‘persons with disabilities and their organizations are critical in the assessment of disaster risk and in designing and implementing plans tailored to specific requirements’.12 The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has published a report highlighting that ‘a disability-inclusive human rights-based approach to climate change entails climate action that is inclusive of and accountable to persons with disabilities at all stages’.13 Previous research also underscores the need for more inclusive climate research that takes disability into account.14

Unfortunately, the representation of persons with disabilities in policy making is insufficient. A mere 39 countries have acknowledged persons with disabilities in their nationally determined contributions, and only 65 countries have made any reference to persons with disabilities in their national adaptation strategies.15 An evaluation of disability-inclusive climate policy making indicates that nations in the Global South generally outperform those in the Global North. Sierra Leone, Zimbabwe, and Cabo Verde rank among the top ten in this assessment.16 The human rights framework in Africa encourages the integration of disability considerations into climate policies. This is demonstrated by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ initiative to conduct the ‘Study on the Impact of Climate Change on Human and Peoples’ Rights in Africa’.17 Additionally, considering that most existing studies primarily concentrate on natural disasters in the United States,18 there is an urgent need for research that encompasses a broader geographical scope. As a result, there is a significant demand for more research on disability-inclusive responses to climate change, specifically in Africa.

The contribution of international human rights monitoring bodies is frequently underestimated in the discourse on disability-inclusive climate action. Given that treaty bodies like the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD Committee) can offer country-specific recommendations, they hold the potential to foster disability-inclusive approaches to climate change. Considering the limited research on the roles of international human rights monitoring bodies in disability-inclusive climate action, this paper seeks to bridge a gap in the literature. It addresses three key questions: Firstly, how does the CRPD Committee ensure the inclusion of persons with disabilities in climate change responses? Secondly, what specific recommendations does the CRPD Committee provide to guarantee the inclusion of persons with disabilities in climate change responses in Africa? Thirdly, how can the connection between climate change and disability rights be fortified in the African context?

2 The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and climate change

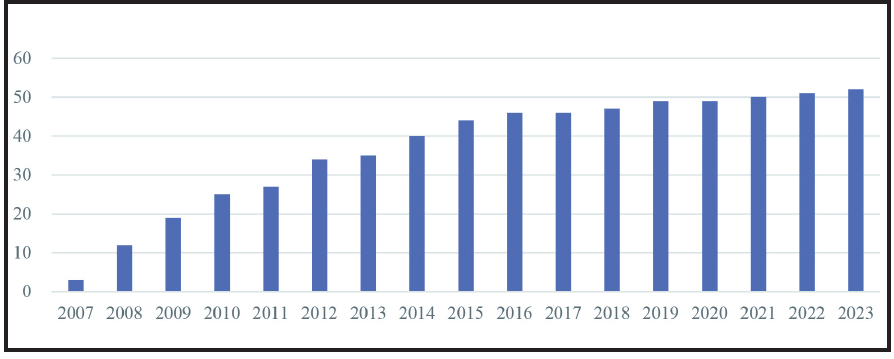

In December 2006, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and its Optional Protocol19 were unanimously approved by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly. The CRPD was put into effect in May 2008. By the close of 2022, the CRPD had been ratified or acceded to by 189 state parties. Most state parties have undertaken a review and revision of their domestic disability laws and have set up national monitoring mechanisms in accordance with the Convention.20 As illustrated in Figure 1, nearly all African nations have ratified or acceded to the CRPD. The widespread adoption of the CRPD underscores the importance of examining disability-inclusive responses to climate change in Africa, utilising the CRPD as a guiding framework.

Figure 1: Cumulative number of African countries that ratified the CRPD21

Although the CRPD does not explicitly mention climate change, its principles of non-discrimination, comprehensive participation, societal inclusion, and accessibility could potentially influence the approach to meeting the needs of persons with disabilities in the context of climate change adaptation and mitigation efforts. The Preamble further stipulates that states must ensure the integration of disability issues as a fundamental component of sustainable development strategies.22 Certain articles are more directly relevant to persons with disabilities in the context of climate change. For example, Article 11 underscores that states are obligated to implement all necessary measures to guarantee the safety and protection of persons with disabilities in risky situations, including humanitarian emergencies:

States Parties shall take, in accordance with their obligations under international law, including international humanitarian law and international human rights law, all necessary measures to ensure the protection and safety of persons with disabilities in situations of risk, including situations of armed conflict, humanitarian emergencies and the occurrence of natural disasters. 23

Moreover, Article 4(3) highlights the states’ general obligations to consult closely with and actively involve persons with disabilities in decision-making processes. This principle could potentially be applied to decisions related to climate change adaptation and mitigation:

In the development and implementation of legislation and policies to implement the present Convention, and in other decision-making processes concerning issues relating to persons with disabilities, States Parties shall closely consult with and actively involve persons with disabilities, including children with disabilities, through their representative organizations. 24

While the ratification of the CRPD marks the beginning of significant change, its effective implementation at the local level is of greater importance.25 Therefore, our attention should be directed towards understanding the workings of the CRPD Committee. The CRPD Committee, composed of independent experts, supervises and offers recommendations to facilitate the Convention’s implementation by state parties. Upon ratification of the Convention, each state party is required to submit regular reports detailing the steps taken to meet its obligations under the Convention and the progress made.26 The Committee then reviews these reports and issues Concluding Observations (COs) to the respective state party, potentially requesting further information about the implementation.27 These procedures enable the identification and resolution of country-specific issues. Consequently, the Convention provides a framework for inclusive climate change solutions by obligating state parties to protect the rights of persons with disabilities.

3 Data

This article utilises data derived from the COs of the CRPD Committee on each country report. Given that each state party receives an annual average of 70 recommendations from various UN human rights monitoring mechanisms, these COs serve as a valuable resource for country-specific information.28 This is why previous studies on the rights of vulnerable groups have analysed COs. For example, Chapman and Carbonetti (2011) examined 135 COs to understand how concerns for the vulnerable have been incorporated into these recommendations.29 Similarly, Lawson and Beckett (2021) examined COs issued by the CRPD Committee to explore the evolving trends from the social model of disability towards the human rights model of disability.30

The author has compiled all the COs from the CRPD Committee for African countries, which are available in the Universal Human Rights Index operated by the OHCHR.31 As of 2022, the CRPD Committee had issued 14 COs on the reports of various African countries, including Tunisia, Gabon, Kenya, Mauritius, Ethiopia, Uganda, Morocco, Sudan, Seychelles, South Africa, Algeria, Niger, Rwanda, and Senegal. Each set of COs is structured into four sections: an introduction, positive aspects, principal areas of concern with recommendations, and follow-up. This study primarily focuses on concerns and recommendations.

The next step involves filtering out all the COs related to climate change. The SDG-Human Rights Data Explorer, a tool developed collaboratively by the OHCHR and the Danish Institute for Human Rights, connects the recommendations of international human rights mechanisms with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).32 This tool facilitates the development of actionable steps to fulfil human rights obligations and sustainable development commitment.33 The database houses a collection of 150 000 recommendations from 67 human rights mechanisms.

As of 2022, the CRPD Committee had issued 6 477 recommendations, with 134 identified as climate-related by the SDGs marker in the SDG-Human Rights Data Explorer. These recommendations serve as the primary data source. However, the categorisation results, obtained through a machine learning process, are not exhaustive.34 The figure was used to corroborate the overall trend. Leveraging the results from the Explorer, the author reviewed all COs in the reports of African countries and broadened the list of climate-related concerns and recommendations.

Furthermore, the author gathered climate-related concerns and recommendations for persons with disabilities from the Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC Committee) and the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW Committee). This information offers insights into how other treaty bodies tackle issues related to specific groups of individuals with disabilities, such as children and women. For example, women with disabilities face additional obstacles to climate adaptation due to gender marginalisation, compared to men with disabilities.

4 Results

4.1 The Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

The CRPD Committee assesses the performance of state parties in meeting their obligations under the Convention. Climate-related concerns and recommendations are specifically addressed in the ‘Situations of Risk and Humanitarian Emergencies’ section of the report. This implies that among the five targets of climate action (SDGs 13), only target 13.1, which aims to strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related disasters, is addressed in the COs produced by the Committee.

Table 1 presents the key points of climate-related concerns and recommendations issued by the CRPD Committee for African countries. The primary climate-related concerns encompass the absence of inclusive emergency and disaster risk reduction strategies and policies for persons with disabilities, the unavailability of information on emergency and disaster strategies in formats accessible to persons with disabilities, and the lack of involvement of persons with disabilities, through their representative organisations, in the formulation and execution of climate change-related policies.

In response to these concerns, the CRPD Committee has put forth three primary climate-related recommendations for African countries. Firstly, there is a call for the development of strategies aimed at mitigating the risks associated with emergencies and disasters, with a specific focus on the inclusion of persons with disabilities. Secondly, it is recommended that information be made accessible and presented in formats comprehensible to persons with disabilities. Lastly, the Committee advocates for the establishment of mechanisms that promote collaboration with organisations representing persons with disabilities.

However, in light of the escalating impacts of climate change on persons with disabilities, the current measures are deemed insufficient. A significant concern is the absence of specific problem analyses and proposals that reflect the unique characteristics of the African region or are tailored to each country’s circumstances. While it is recognised that most countries face similar climate change challenges, the content of the proposal needs to be more region- or country-specific to improve its feasibility. Persons with albinism, for instance, are more prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa and may face a higher risk of developing skin cancer due to climate change.35 However, persons with albinism are not mentioned in 14 COs of African countries.

As previously noted, apart from target 13.1, the other targets of SDG 13 are not addressed in the COs issued by the CRPD Committee. However, these targets are addressed by other treaty bodies. For instance, the CRC Committee recommends that Cambodia enhance children’s awareness of climate change by integrating environmental education into the school curriculum. This recommendation aligns with SDGs target 13.3, which emphasises the need to build knowledge and capacity to tackle climate change challenges. 36

Next, it is important to note that international collaboration on climate change has not been mentioned in any recommendations for African countries. Article 32 of the Convention highlights the significance of international cooperation, ensuring inclusivity and accessibility for persons with disabilities.37 The general principles of international cooperation are deemed a vital strategy for advancing the rights of persons with disabilities. For example, the CRPD Committee recommends that Morocco implement measures to guarantee the effective participation, inclusion, and consultation of persons with disabilities within the framework of international cooperation programmes.38 Despite the emphasis on promoting international cooperation, previous recommendations in Africa have not specifically addressed international collaboration on climate change.

In conclusion, COs in the region often classify persons with disabilities as a homogeneous group. However, the intersection of various discriminatory factors, including gender, age, displacement, and indigenous origin can intensify the risks that persons with disabilities face in experiencing the adverse effects of climate change.39 Therefore, while it is crucial to address issues common to persons with disabilities, it is equally important to highlight issues that reflect the diverse types and intersectional nature of disability. Adopting a disaggregated approach can lead to more precise problem identification and alternative solutions. Furthermore, examining issues that reflect intersectionality - such as women with disabilities, children with disabilities, and older individuals with disabilities - can pave the way for collaboration with other UN human rights treaty bodies, including those advocating for women and children.

However, only a handful of references are made to specific sub-groups of disabilities in relation to climate-related issues. These findings align with the observation that UN treaty bodies often focus on singular identities, thereby understating the diverse characteristics of individuals.40 A notable exception is the 2016 recommendation for Uganda, which stresses addressing the needs of refugees with disabilities in humanitarian emergencies.41 In 2018, a recommendation was made for Sudan to extend aid to persons with disabilities. This aid specifically targets those who are internally displaced, refugees, or asylum seekers.42 The 2019 recommendation for Senegal underscores that individuals who are deaf, those with psychosocial or intellectual disabilities warrant special attention.43 Despite these examples, the majority of COs do not specifically target certain sub-groups of disabilities with climate-related concerns.

Table 1: Climate-related concerns and recommendations by the CRPD Committee for African countries44

4.2 Other UN treaty bodies

To understand how issues concerning children with disabilities and women with disabilities are addressed in other UN treaty bodies, the author examined the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC Convention) and the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW Convention). While neither Convention directly tackles climate change, they embody principles that apply to the issue, similar to the CRPD. The CRC Convention outlines specific rights related to the environment, including the right to non-discrimination, the best interests of the child, the right to life, the right to be heard, access to information, and the rights of Indigenous children and children from minority groups, among others.45 It is noteworthy that the CRC Committee’s most recent COs contain a separate section on the effects of climate change on children’s rights. The CEDAW Convention also includes general principles applicable to disaster risk reduction and climate change, such as substantive equality and non-discrimination, participation and empowerment, and accountability and access to justice. 46

Recently, both the CRC and CEDAW Committees have made significant contributions to the discourse on climate change and its impact on vulnerable groups, each publishing a general comment or recommendation. In 2023, the CRC Committee approved a general comment on climate change, aiming to highlight the urgent need to mitigate its adverse effects on children’s rights. This comment promotes a comprehensive understanding of children’s rights in the context of environmental protection and clarifies the obligations of states under the Convention, with a particular emphasis on climate change.47 The general comment emphasises that specific groups of children, including those with disabilities, encounter increased obstacles in exercising their rights. The detrimental effects of environmental harm disproportionately impact these children.48 Additional support and specialised strategies may be necessary to empower children in disadvantaged situations, such as those with disabilities, to exercise their right to be heard.49 Furthermore, neither the design nor the implementation of adaptation measures should discriminate against children at heightened risk, such as those with disabilities. 50

In a similar vein, the CEDAW Committee published a general recommendation on climate change in 2018. This recommendation underscores the significant challenges and opportunities that climate change and disaster risk present for the realisation of women’s human rights.51 The general recommendation emphasises that women and girls with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to gender-based violence and sexual exploitation during and in the aftermath of disasters.52 The recommendation also advocates that state parties should ensure that all policies related to disaster risk reduction and climate change are responsive to gender, with a focus on the most marginalised groups of women and girls, including those with disabilities.53 In terms of more specific measures, the recommendation highlights the importance of early warning information. This information should be provided using technologies that are timely, culturally appropriate, accessible, and inclusive, ensuring accessibility for all women, including those with disabilities.54

An exploratory analysis of climate-related recommendations for African countries from the CRC and CEDAW Committees yields insightful results. The CRC Committee has issued a total of 238 climate action-related recommendations, 47 of which are specifically designed for persons with disabilities. The primary recommendation urges the state party to allocate strategic budgetary resources for children in disadvantaged or vulnerable situations, including children with disabilities. The CEDAW Committee has issued a total of 186 climate change-related recommendations, 15 of which are specifically aimed at persons with disabilities. The primary recommendation is that the state party should ensure the inclusion of all women, including women with disabilities, in the development and implementation of national policies and programmes related to climate change. These findings demonstrate that these committees are addressing the issues related to children and women with disabilities. They also underscore the importance of enhancing climate action through an intersectional approach. Furthermore, these results highlight the need for collaborative efforts to incorporate disability-inclusive climate actions into the frameworks of UN human rights treaties.

5 Conclusion

This paper explores the role of the CRPD Committee in promoting disability-inclusive responses to climate change in Africa. The CRPD Committee consistently emphasises the inclusion of persons with disabilities in climate change responses in its COs on country reports. Key recommendations include the implementation of emergency and disaster risk reduction strategies, the provision of information in accessible formats, and the establishment of engagement channels with disability representative organisations. However, the unique characteristics of the African region or individual countries are not sufficiently considered. Several critical issues related to climate change remain unaddressed. There is a need to tackle additional issues such as the significance of international cooperation and heightened focus on the sub-groups of disabilities with climate-related concerns.

These findings provide valuable insights that reinforce the connection between climate change and disability rights within the CRPD Committee. The implications of this study are threefold. Firstly, it underscores the need to develop comprehensive recommendations that ensure the inclusion of persons with disabilities in the CRPD Committee’s responses to climate change. The CEDAW and the CRC Committees have shown that making general recommendations can advance the integration of climate change into the discourse on disability rights. The Committee’s review process and the issuance of COs should incorporate a general comment or recommendation on disability-inclusive climate action. By adding a separate section on the effects of climate change on disability rights in the COs, the CRPD Committee would enhance its role in promoting more inclusive responses to climate change.

Secondly, it is crucial to recognise the diversity within the group of persons with disabilities. The intersectionality of age, gender, and disability leads to unique experiences and challenges that must be considered in the CRPD Committee’s overall approach to climate action. Thirdly, it emphasises the importance of an international climate change collaboration strategy that includes persons with disabilities, particularly in the African context.

Strengthening the connection between climate change and disability rights within the CRPD Committee would contribute to mainstreaming disability-inclusive climate action within Africa’s human rights framework, such as the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in Africa (African Disability Protocol). The recent coming into force of the African Disability Protocol provides an enabling regional framework for integrating disability considerations into climate policies.55 Strengthening the role of the CRPD Committee, along with ongoing efforts to enhance human rights frameworks at the continental level, is essential for mainstreaming disability-inclusive climate action in Africa.

One of the limitations of this study is its exclusive focus on the African region. While this study highlights the situation in Africa, it underscores the need for geographically broader research into the role of the CRPD Committee in fostering disability-inclusive responses to climate change. Another limitation of this study is that its analysis of climate-related recommendations for the CRC and CEDAW Committees is merely exploratory. This paper also advocates for additional comparative studies and case studies on the CEDAW Committee, the CRC Committee, and the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. These studies could contribute to a comprehensive examination of disability-inclusive responses to climate change by international human rights monitoring bodies.

1. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change ‘Decision 1/CP.21 Adoption of the Paris Agreement’ 29 January 2016, UN Doc FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1 (2016) (Paris Agreement), Preamble.

2. ‘How Africa will be affected by climate change’ BBC 15 December 2019 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-50726701 (accessed 27 January 2024).

3. African Union ‘African Union Climate Change and Resilient Development Strategy and Action Plan 2022-2032’ (2023).

5. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction ‘Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030’ (2015).

6. PJS Stein & MA Stein ‘Disability, human rights, and climate justice’ (2022) 44 Human Rights Quarterly 81.

8. Centre for International Environmental Law ‘The rights of persons with disabilities in the context of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change’ (2019) 6.

9. PJS Stein and others ‘Advancing disability-inclusive climate research and action, climate justice, and climate-resilient development’ (2024) 8 The Lancet Planetary Health e242.

10. B Astle and others ‘Global impact of climate change on persons with albinism: A human rights issue’ (2023) 9 The Journal of Climate Change and Health 100190.

11. PJS Stein & MA Stein ‘Climate change and the right to health of people with disabilities’ (2022) 10 Lancet Global Health e24.

13. Human Rights Council, Analytical study on the rights of persons with disabilities in the context of climate change, 22 April 2020, UN Doc A/HRC/44/30 (2020) para 39.

14. See S Jodoin and others ‘Nothing about us without us: The urgent need for disability-inclusive climate research’ (2023) 2 PLOS Climate e0000153; PJS Stein and others ‘The role of the scientific community in strengthening disability-inclusive climate resilience’ (2023) 13 Nature Climate Change 108; Stein & Stein (n 11).

17. African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights ‘Call for comments to the study on the impact of climate change on human and peoples’ rights in Africa’ (2023) https://achpr.au.int/en/news/press-releases/2023-10-28/call-comments-study-impact-clima te-change-human-and-peo (accessed 18 July 2024).

18. CJ Gaskin and others ‘Factors associated with the climate change vulnerability and the adaptive capacity of people with disability: A systematic review’ (2017) 9 Weather, Climate, and Society 801.

19. United Nations General Assembly, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 24 January 2007, UN Doc A/RES/61/106 (2007).

21. Drawing upon data from the United Nations Treaty Collection ‘Status of treaties’ https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-15&ch apter=4&clang=_en (accessed 27 January 2024).

25. S Jodoin and others ‘A disability rights approach to climate governance’ (2020) 47 Ecology Law Quarterly 73.

28. Danish Institute for Human Rights ‘SDG-human rights data explorer methodology’ https://sdgdata.humanrights.dk/en/methodology (accessed 27 January 2024).

29. AR Chapman & B Carbonetti ‘Human rights protections for vulnerable and disadvantaged groups: The contributions of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights’ (2011) 33 Human Rights Quarterly 682.

30. A Lawson & AE Beckett ‘The social and human rights models of disability: Towards a complementarity thesis’ (2021) 25 The International Journal of Human Rights 348.

31. OHCHR ‘The Universal Human Rights Index (UHRI)’ https://uhri.ohchr.org/en/ (accessed 27 January 2024).

32. Danish Institute for Human Rights ‘SDG-human rights data explorer: Explore data’ https://sdgdata.humanrights.dk/en/solr-explorer (accessed 27 January 2024).

33. Danish Institute for Human Rights ‘What is the SDG-human rights data explorer?’ https://sdgdata.humanrights.dk/en/node/23 (accessed 27 January 2024).

36. CRC Committee, Concluding observations on the combined fourth to sixth periodic reports of Cambodia, 27 June 2022, UN Doc CRC/C/KHM/CO/4-6 (2022) para 39.

38. CRPD Committee, Concluding observations on the initial report of Morocco, 25 September 2017, UN Doc CRPD/C/MAR/CO/1 (2017) para 61.

40. G de Beco ‘Intersectionality and disability in international human rights law’ (2020) 24 The International Journal of Human Rights 593.

41. CRPD Committee, Concluding Observations on the initial report of Uganda, 12 May 2016, UN Doc CRPD/C/UGA/CO/1 (2016) para 21.

42. CRPD Committee, Concluding Observations on the initial report of the Sudan, 10 April 2018, UN Doc CRPD/C/SDN/CO/1 (2018) para 21.

43. CRPD Committee, Concluding Observations on the initial report of Senegal, 13 May 2019, UN Doc CRPD/C/SEN/CO/1 (2019) para 20.

44. Source: COs of the CRPD Committee on the reports of Tunisia, Gabon, Kenya, Mauritius, Ethiopia, Uganda, Morocco, Sudan, Seychelles, South Africa, Algeria, Niger, Rwanda, and Senegal. COs for Tunisia in 2011 did not include any concerns or recommendations related to climate change.

45. United Nations General Assembly, Convention on the Rights of the Child, 20 November 1989, General Assembly Resolution 44/25 (1989).

46. United Nations General Assembly, Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, 18 December 1979, General Assembly Resolution 34/180 (1979).

47. Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment 26 on children’s rights and the environment with a special focus on climate change, 22 August 2023, UN Doc CRC/C/GC/26 (2023) para 12.

51. Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, General Recommendation 37 on Gender-related dimensions of disaster risk reduction in the context of climate change, 7 February 2018, UN Doc CEDAW/C/GC/37 (2018) para 8.

55. See African Union, Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in Africa (2018) art 12; Centre for Human Rights ‘Press statement: Centre for Human Rights welcomes the coming into force of the African Disability Protocol’ (2024) https://www.chr.up.ac.za/latest-news/3877-press-statement-the-centre-for-human-rights-welcomes-the-coming-into-force-of-the-african-disability-protocol (accessed 8 October 2024).