- Ilze Grobbelaar-du Plessis

- BIuris LLB LLM LLD (UP)

- Associate Professor, Department of Public Law, University of Pretoria, and member of the advisory committee of the South African Law Reform Commission (SALRC) on Project 148 regarding the domestication of the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)

- I Grobbelaar-du Plessis ‘Country report: South Africa’ (2023) 11 African Disability Rights Yearbook 115-145

- https://doi.org/10.29053/adry.v11i1.5105

- Download article in PDF

1 Population indicators

1.1 What is the total population of South Africa?

According to the Census 2011, conducted by Statistics South Africa (StatsSA)1 more than a decade ago, the total population of South Africa was 51.8 million.2 The latest census by StatsSA was conducted from March to April 2022,3 but the official Census 2022 data was not available at the time of writing this country report.4

However, StatsSA reported a positive population growth rate by the end of June 2022, despite the devastating impact of COVID-19 globally.5 StatsSA’s mid-year population estimate of 60.6 million did not include inputs from the latest Census conducted from March-April 2022. According to the 2022 World Bank data, the population of South Africa was estimated at 59 893 885.6

1.2 Describe the methodology used to obtain the statistical data on the prevalence of disability in South Africa. What criteria are used to determine who falls within the class of persons with disabilities in South Africa?

Statistical data on the prevalence of disability in South Africa is used from StatsSA, which is mandated to provide government and other stakeholders with official statistics on the demographic, economic and social situation of the country to support planning, monitoring and evaluation of the implementation of programmes and initiatives.7 In fulfilling its mandate prescribed in the Statistics Act,8 StatsSA conducted four Censuses in 1996, 2001, 2011, and 2022 respectively.9 In the Census 2001, measurement of disability was based on the definition from the 1980 World Health Organisation (WHO) International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps (ICIDH). The ICIDH defined ‘disability’ as a physical or mental handicap which has lasted for six months or more, or is expected to last at least six months, which prevents the person from carrying out daily activities independently, or from participating fully in education, economic, or social activities.10 The Census 2001 used the terminology of ‘disabled’ and the data gathered reflects the prevalence of certain disabilities.11 Two studies were conducted in preparation for the Census 2011 to test the applicability in South Africa of the Washing Group (WG) Short Set of Questions on Disability. The result of both studies showed that the use of the WG questions led to far higher disability estimates compared to the traditional question of ‘do you have a serious disability that prevents your full participation in life activities?’12 Subsequently, studies recommended the use of the WG questions for Census 2011.13 This means that Census 2011 did not only measure severe disabilities, as the term ‘difficulty’ was used and not the traditional terminology of ‘disabled’.14 Disabilities were defined as ‘difficulties encountered in functioning due to impairments or activity limitation, with or without assistive devices’.15 As a result of the change in approach of asking disability questions, the Census 2011 data were not comparable with previous Censuses.16 Furthermore, the definition used does not comply either with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD),17 ratified by South Africa in 2007, or the White Paper on an Integrated National Disability Strategy (INDS). 18

Following Census 2011, the 2014 monograph of StatsSA, Census 2011: Profile of persons with disabilities in South Africa, provides a comprehensive profile of persons with disabilities in South Africa, exploring key aspects pertaining to its demographics, socio-economic status as well as its health status in terms of functions.19 Furthermore, differentials and spatial distributions by sex, population group and geographical location profiled bring critical issues pertaining to the well-being of this vulnerable group forth.20 The report provided statistical evidence relating to the prevalence of disability and characteristics of persons with disabilities at both individual and household levels, based on the Census 2011 data. Two measures were employed to profile disability prevalence and patterns. The measures were i) the levels or degree of difficulty in a specific functional domain, which were based on the six functional domains, namely seeing, hearing, communication, remembering, or concentrating, walking, and self-care; and ii) the disability index.21

However, it must be noted that StatsSA indicates that the report did not include statistics on children under the age of five or persons with psychosocial and certain neurological disabilities due to data limitations. The report should therefore not be used for purposes of describing the overall disability prevalence or profile of persons with disabilities in South Africa.22 In South Africa’s Initial Report on the Implementation of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) to the CRPD’s monitoring body (the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD Committee)),23 it was noted that the lack of adequate, reliable, relevant, and recent information on the nature and prevalence of disability in South Africa remained a challenge. 24

1.3 What is the total number and percentage of persons with disabilities in South Africa?

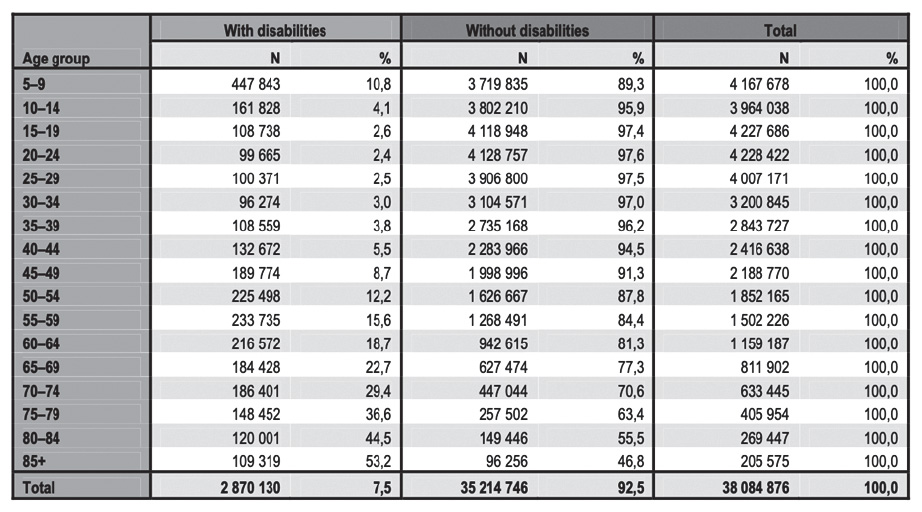

See question 1.2 above. However, StatsSA’s in-depth 2014 report on persons with disabilities reported the national disability prevalence rate is 7.5 per cent. According to the report disability positively correlated with age, as persons with disabilities increase with age. More than half (53.2 per cent) of persons aged 85+ reported to have a disability. 25

1.4 What is the total number and percentage of women with disabilities in South Africa?

See question 1.2 above. StatsSA reported in its 2014 report regarding Census 2011: Profile of persons with disabilities in South Africa that disability was more prevalent among females compared to males (8.3 per cent and 6.5 per cent respectively).26

1.5 What is the total number and percentage of children with disabilities in South Africa?

See question 1.2 above. The Census 2011: Profile of persons with disabilities in South Africa report by Stats SA did not include statistics on children under the age of five or on persons with psychosocial and certain neurological disabilities due to data limitations.27

The result in the table28 above showed slightly higher rates in the 5-9-year-old age group. However, the report warned that caution should be exercised in interpreting these results. It was noted that parents misreported on children by categorising them as either ‘unable to do’ and/or ‘having a lot of difficulty to perform certain functions’, when in reality this is an aspect that can be attributed to the child’s level of development rather than an impairment. 29

1.6 What are the most prevalent forms of disability and/or peculiarities to disability in South Africa?

According to the Census 2011: Profile of persons with disabilities in South Africa report, the prevalence of a specific type of disability shows that 11 per cent of persons aged five years and older had seeing difficulties, 4.2 per cent had cognitive difficulties (remembering or concentrating), 3.6 per cent had hearing difficulties, and about 2 per cent had communication, self-care, and walking difficulties. Therefore, from the Census 2011, seeing difficulties was reported to be the most prevalent difficulty. However, it must be noted that the majority reported mild difficulty (9.3 per cent).30

2 South Africa’s international obligations

2.1 What is the status of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) in South Africa? Did South Africa sign and ratify the CRPD? Provide the date(s).

South Africa signed the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and Optional Protocol on 30 March 2007 and subsequently ratified both the Convention and the Optional Protocol on 30 November 2007. No reservations to the CRPD or its Option Protocol were recorded.31

2.2 If South Africa has signed and ratified the CRPD, when is/was its country report due? Which government department is responsible for the submission of the report? Did South Africa submit its report? If so, and if the report has been considered, indicate if there was a domestic effect of this reporting process. If not, what reasons does the relevant government department give for the delay?

The Department of Women, Children and People with Disabilities (DWCPD) was responsible for submitting the report. South Africa’s Initial Report was due two years after the CRPD entered into force, which means that it was due by May 2010. However, the first draft country report to the United Nations (UN) on the implementation of the CRPD was released on 26 November 2012 for public comment. The aim was to complete and deposit the first Initial Report to the CRPD Committee by March 2013. At the time, the reason for the delay in submission of the report was due to changes in organisational arrangements with the transition from the Office on Status of Disabled People (OSDP) to the DWCPD. This transition had a negative impact on the finalisation and deposit of the report within the two-year post ratification time specified in the CRPD.32 The Initial Report was submitted on 26 November 2014 to the CRPD Committee.33

The South African government, reported that the INDS in 1997, developed through a widely-consultative process applying the UN Standard Rules on Equalisation of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities, as well as the South African Disability Rights Charter, provided guidelines for mainstreaming of disability across all government departments as legislative and policy reform in the newly-established democratic South Africa took effect.34 According to the Initial Report, the South African government reported that since the CRPD embodies principles of the South African process which was set in motion in 1994 to advance the progressive realisation of the rights of persons with disabilities as equal citizens, the implementation of the CRPD actually commenced in 1994 and not in 2007.35

However, the CRPD Committee noted in its Concluding Observation that was adopted in September 2018,36 that the South African government undertook an audit of its laws and policies to bring them into line with the human rights model of disability, including the comprehensive White Paper on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities of 2015. The White Paper aims to accelerate change and redress with regard to the full inclusion, integration, and equality of persons with disabilities.37 Furthermore, the interrelatedness of disability and poverty was articulated in South Africa’s National Development Plan (NDP), which was adopted in 2012. The NDP recognises that many persons with disabilities are not able to develop their full potential due to a number of barriers that have to be addressed. 38

2.3 While reporting under various other United Nations instruments, or under the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, or the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, did South Africa also report specifically on the rights of persons with disabilities in its most recent reports? If so, were relevant ‘Concluding Observations’ adopted? If relevant, were these observations given effect to? Was mention made of disability rights in your state’s UN Universal Periodic Review (UPR)? If so, what was the effect of these observations/recommendations?

UN Instruments

- Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)39

South Africa signed and in 1995 ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). In 1997 South Africa submitted the Initial Report, and in early 2000 the Concluding Observations were adopted. In the Concluding Observations of the monitoring body of the CRC, the Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC Committee)40 mentioned in several instances the rights of children with disabilities. Firstly, mention was made of the positive aspect of ‘Curriculum 2005’, which aimed at facilitating a more inclusive school environment, including programmes to encourage non-discrimination, especially of children with disabilities. However, there were also concerns raised that the data collection mechanism was insufficient for purposes of the areas covered by the CRC. The CRC Committee in particular highlighted data collection mechanisms in relation to all groups of children in order to monitor and evaluate progress achieved and assessments made of the impact of policies adopted with respect to children. The CRC Committee subsequently recommended that the system of data collection had to be reviewed with a view to incorporate all the areas covered by the CRC.41 The CRC Committee also noted that the principle of non-discrimination, in article 2 of the CRC, is reflected in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (the Constitution) and South African legislation, but there are insufficient measures in place to ensure that all children are guaranteed access to education, health, and other social services.42 Of particular concern were certain vulnerable groups of children such as children with disabilities, especially those with learning disabilities. The recommendation made by the Committee was that South Africa must increase its efforts to ensure the proper implementation of the non-discrimination article.43 Lastly, the CRC Committee raised concerns that the legal protection, facilities, and services for children with disabilities, and particularly mental disabilities, are insufficient. The CRC Committee’s recommendations, amongst others, were that South Africa should reinforce its early identification programmes to prevent disabilities, establish special education programmes for children with disabilities, and further encourage their inclusion in society. Furthermore, the CRC Committee recommended that government seeks technical cooperation for the training of professional staff working with and for children with disabilities from, inter alia, the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and WHO.44

In part 6 of South Africa’s Periodic Country Report on the CRC for the period January 1998 to April 2013, the DWCPD provided detailed feedback on the CRC Committee’s Concluding Observations.45 In the CRC Committee’s Observations on the second periodic report of South Africa, the Committee welcomed the ratification of the CRPD by South Africa in 2007, as well as the adoption of the Framework and Strategy for Disability and Rehabilitation Services in South Africa 2015-2020. Nevertheless, the CRC Committee remained concerned with: i) the multiple layers of discrimination and exclusion faced by the majority of children with disabilities in South Africa; ii) the lack of accurate and comprehensive data on children with disabilities; iii) insufficient and/or comprehensive law and policy to realise the rights of children with disabilities, with clear baselines, clear time frames, and measurable indicators for the implementation, as well as mechanisms for monitoring implementation; iv) the absence of effective multisectoral coordination within government, in particular in rural areas, to provide integrated services to children with disabilities; and v) the lack of effective provision of reasonable accommodation, such as through the provision of assistive devices and of services in Braille and in sign languages. 46

The CRC Committee further welcomed the efforts made to provide inclusive education to all children, including children with disabilities, by developing full-service schools. However, the Committee remained concerned and made recommendations regarding the lack of legislation to affirm the right to inclusive basic education for all children with disabilities; ineffective implementation of relevant policies due to acute shortages of staff with expertise on disabilities and insufficient allocations of financial resources; failure to provide free, compulsory primary education to children with disabilities; the large number of children with disabilities who are out of school or are studying in specialised schools or classes, in particular children with psychosocial disabilities; discrimination and violence by teachers and by other students, against children with disabilities; and the low quality of education provided and inadequate curriculum content used for children with disabilities, particularly children with psychosocial disabilities, autism spectrum disorders, and sensory disabilities, which does not equip them with the capacity to pursue higher education, employment, and an autonomous life after they have completed their schooling. 47

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW)48

South Africa signed and in 1995 ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). South Africa’s latest Country Report was submitted in May 2019,49 where the South African government reported to have launched public education initiatives to raise awareness of legal recourse and redress measures available to, amongst others, women with disabilities. They reported that a combination of various communication platforms was utilised such as media; public exhibitions; educational imbizos and government websites to promote the rights of women, children, older persons, persons with disabilities, the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Intersex (LGBTQI) community, and other marginalised groups.50 It was further reported that educational materials are printed in Braille including booklets and the Braille version of the Constitution. Forms prescribed by Regulations for the Domestic Violence Act51 have been translated into all 11 official languages and distributed to all lower courts in the country. It was further reported that in November 2014 a round-table discussion on ‘Equal Access to Justice for Persons with Disabilities’ was held.52 The South African government also reported that it provides annual training interventions on legislation promoting the rights of women and children. Amongst others, intermediaries were trained in information management on cases of sexual offences involving child victims and persons with mental disabilities.53 Furthermore, the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA) Act,54 continues to be implemented and provides for income transfer in the form of different kinds of social grants such as a disability grant; a grant for older persons and a war veteran’s grant; foster child grant; care dependency grant; child support grant; and a grant-in-aid through direct and unconditional cash transfers. The social grant programme was reported to have resulted in a reduction in poverty levels in vulnerable groups. 55

In the Concluding Observations of the monitoring body of CEDAW, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW Committee), on the fifth periodic report of South Africa,56 noted with concern the high risk of gender-based violence against women and girls facing intersecting forms of discrimination, such as lesbian, bisexual and transgender women and intersex persons, refugee women, women with disabilities and women and girls with albinism and urged the government raise awareness.57 Furthermore, the CEDAW Committee recommended that the South African government raise awareness among women, including women belonging to ethnic minorities, women with disabilities, migrant women, and lesbian, bisexual and transgender women, about the legal remedies available to them in the event of discrimination.58 The CEDAW Committee recommended that government should provide capacity-building in political leadership and campaigning skills and access to campaign financing for women candidates, including women with disabilities and women with albinism. In this regard, the CEDAW Committee recommended that government raise awareness among political leaders and the public about the fact that the full, equal, free, and democratic participation of women in political and public life on an equal basis with men is required for the full implementation of the CEDAW.59 The CEDAW Committee noted with concern that girls, in particular girls with disabilities, continue to face gender-based violence and discrimination in the school environment and unsafe transportation to and from schools.60 The Committee recommended that the South African government ensure that women with disabilities, amongst others, have affordable access to sexual and reproductive health services, including safe abortion and post-abortion services, free from gender-based violence, discrimination, or harassment.61

On disadvantaged groups of women, the CEDAW Committee further recommended that the South African government provide information in its next periodic report on the situation of women facing intersecting forms of discrimination, including lesbian, bisexual, and transgender women and intersex persons, migrant, refugee and asylum-seeking women, women living with HIV/AIDS, women with disabilities, and women with albinism, and on measures taken to address such discrimination. 62

Regional instruments

South Africa signed and ratified the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) in 1996 and presented its periodic report in 2005. According to article 18 of the ACHPR, the ‘aged and disabled shall also have the rights to special measures of protection in keeping with their physical needs’. In the South African government’s first Periodic Report, it was mentioned that South Africa had tried to comply with article 18 of the Charter.63 The second Periodic Report (combining the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth reports) captured the developments within South Africa on the realisation of the rights guaranteed by the Charter from 2002 to the end of 2013, as well as responses to the Concluding Observations adopted by the African Commission in December 2005.64 The report included information and data pertaining to disability as captured in the Census 2011; the adoption of the 1997 INDS; the Job Access Strategy 2006-2010 adopted by Cabinet in 2007; the positive measures to ensure the economic and social needs of persons with disabilities through the disability grant in terms of the Social Assistance Act;65 as well as free healthcare.66

In the Concluding Observations with recommendations on the combined second Periodic Report under the ACHPR and the Initial Report under the Protocol to the African Charter on the Rights of Women in Africa of the Republic of South Africa to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights,67 the Commission commends enactment of legislation to ensure equality in a variety of areas including disabilities,68 and commends the social policies and other measures taken in favour of vulnerable or designated groups such as the Policy on Disability,69 and the adoption of the Disability Framework for Local Government 2009-2014.70 However, the Commission was concerned about the lack of adequate disaggregated data on, amongst others, disability and other elements that are important in formulating policies for persons with disabilities.71 The Commission recommended that the South African government should provide adequate disaggregated data in its next Periodic Report on the gender, age, type, and other elements that are important in formulating policies for the disabled. 72

South Africa’s human rights record was last reviewed by the UN Human Rights Council’s Periodic Review (UPR) Working Group in November 2022 (fourth UPR Review). South Africa’s first, second, and third UPR reviews took place in April 2008, May 2012, and May 2017 respectively. These reviews are based on national reports - information provided by the State under review; information contained in the reports of independent human rights experts and groups, known as the Special Procedures, human rights treaty bodies, and other UN entities; information provided by other stakeholders including national human rights institutions, regional organisations, and civil society groups.73

South Africa, in the country’s national report submitted to the Human Rights Council,74 responded to 243 recommendations issued during the third cycle review report in 2017.75 On recommendations regarding economic, social, and cultural rights, the South African government reported that the Social Assistance Amendment Act76 aims to provide for additional social assistance payments. South Africa spends about R180 billion per year on social grants targeting poor children, the elderly, and those with a disability. In addition to this, during 2020/21, a Special COVID-19 Social Relief package estimated at R55 billion was implemented to assist lower-income households during the pandemic. This included a new grant for those between the ages of 18 and 60 and caregivers’ allowance for those receiving a Child Support Grant, who are mostly women. While this was a temporary relief measure, the new grant, with some amendments to improve the gender aspects of the grant, was extended to March 2022; and the government is engaged in ongoing dialogue around the possibility of providing more permanent social assistance for this cohort. 77

The Human Rights Council Periodic Review Working Group’s recommendations were adopted on 9 March 2023.78 It is worth mentioning that the recommendations by the Working Group regarding the protection of vulnerable groups which include children, persons with disabilities, and LGBTQIA+, were supported or accepted by South Africa.79

2.4 Was there any domestic effect on South Africa’s legal system after ratifying the international or regional instrument in 2.3 above? Does the international or regional instrument that had been ratified require South African legislature to incorporate it into the legal system before the instrument can have force in South Africa’s domestic law? Have the courts of South Africa ever considered this question? If so, cite the case(s).

South Africa is a constitutional democracy. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (the Constitution) remains the overarching normative framework to transform the South African society. The Constitution includes provisions on the role of international law with regard to the interpretation of the Bill of Rights (Chapter 2 of the Constitution) and statutory interpretation. Section 39(1) of the Constitution provides that when interpreting the Bill of Rights, a court, tribunal, or forum must promote the values that underlie an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality, and freedom; must consider international law; and may consider foreign law. Furthermore, section 231(1) of the Constitution provides that the negotiating and signing of all international agreements is the responsibility of the national executive. According to section 231(2) of the Constitution, an international agreement binds the Republic only after it has been approved by resolution in both houses of the National Legislature (Parliament), which means that it has to be approved by the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces. The effect is that an international agreement that had been ratified by resolution of Parliament is binding on South Africa on the international plane. Failure to observe the provisions of the international agreement may result in South Africa incurring responsibility towards other signatory states.80 However, section 231(4) of the Constitution provides that any international agreement becomes law in the Republic when it is enacted into law by national legislation. It is clear from the constitutional provision that South Africa follows a dualistic approach and requires the incorporation of international instruments into domestic law when it is enacted into law by national legislation (Act of Parliament).81 This was confirmed by the Constitutional Court in Glenister v President of the Republic of South Africa (Glenister):82

An international agreement that has been ratified by Parliament under section 231(2) (of the Constitution), however, does not become part of our law until and unless it is incorporated into our law by national legislation. An international agreement that has not been incorporated in our law cannot be a source of rights and obligations. As this Court held in AZAPO ‘[an] international convention does not become part of the municipal law of our country, enforceable at the instance of private individuals in our courts, until and unless they are incorporated into the municipal law by legislative enactment’.

In Glenister, the Constitutional Court confirmed that South Africa requires legislative incorporation of an international agreement in order for the agreement to create rights and obligations under domestic law.83 The legislative act which incorporates the international agreement, such as the CRPD, into domestic law has the effect of transforming an international obligation that binds the sovereign at the international level, into domestic legislation that binds the State and citizens as a matter of domestic law.84 For purposes of persons with disabilities living in South Africa, it means that an Act of Parliament has to incorporate the CRPD into domestic law in order to transform the international obligations into domestic legislation that binds the South African government and citizens.85 Of further importance is section 233 of the Constitution which provides that when interpreting any legislation, every court must prefer any reasonable interpretation of the legislation that is consistent with international law over any alternative interpretation that is inconsistent with international law.

South Africa ratified or acceded to many international human rights instruments, and in compliance with International Treaty obligations, presented its country reports to the applicable UN human rights treaty monitoring body. Furthermore, it should be noted that South Africa’s human rights record was reviewed by the UPR Working Group’s first, second, third and fourth UPR cycle reviews in April 2008, May 2012, May 2017, and November 2022 respectively.86 In applying its duties and obligations in terms of the international instruments, the South African government is committed to undertake a series of measures to end discrimination in the South African society,87 and to address the promotion, protection, and fulfilment of its international human rights obligations.88 Additional to international human rights instruments, South Africa has ratified regional human rights instruments and submitted reports as part of its compliance with the continental instruments’ mechanisms.89 Most of the international and regional human rights instruments have been reported to either been domesticated through specific legislation, or through already enacted legislation that accommodated the principles contained in the instruments. 90

2.5 With reference to 2.4 above, has the United Nations CRPD or any other ratified international instrument been domesticated? Provide details.

See question 2.4 above. The South African government has worked consistently to ensure gradual improvement in addressing both procedural and substantive gaps in its quest for the promotion, protection, and fulfilment of international human rights obligations.91 The South African government reported in the second cycle of its periodic review to the UPR Working Group of May 2012 that satisfactory progress was made in the development of legislation in the advancement of human rights protection,92 and the domestication thereof is reported on during the cycle reviews to the Working Group.93

As previously mentioned, South Africa signed the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and the Optional Protocol on 30 March 2007. Ratifications of both the Convention and the Optional Protocol followed on 30 November 2007.94 South Africa submitted its Initial Report under article 35 of the Convention to the CRPD Committee on 26 November 2014. The CRPD Committee welcomed the Initial Report of South Africa, which was prepared in accordance with the Committee’s reporting guidelines and thanked the State Party for its written replies to the list of issues prepared by the Committee.95

The CRPD Committee then considered the Initial Report of South Africa on 28 and 29 August 2018 and adopted its Concluding Observations to the report on 7 September 2018.96 However, although South Africa is bound by the reporting obligations,97 neither the CRPD nor its Optional Protocol has been incorporated into South African law (see para 2.4 above). For this purpose, the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (DOJ&CD) requested the South African Law Reform Commission (SALRC)98 in May 2018 to investigate the domestication of the CRPD. 99

The SALRC deals with complex, crosscutting investigations where innovative constitutional reform is necessary or legislative coordination is needed. Often this falls outside the mandate of a specific South African governmental department. Domestication of the CRPD struggled to get off the ground since it was ratified in 2007 and the SALRC was given the mandate to investigate the domestication of the CRPD as stated above. The SALRC follows a three-stage process, where the first stage of the process is the development of an issue paper, which sets out the issues pertaining to the subject of the investigation.100 The discussion paper is developed during the second stage on the strength of the responses received on the issue paper. This paper, on the strength of the responses, develops a preliminary view and goes out for public consultation. It is important to note that during the third stage of the process, the responses on the discussion paper will result in the formulation of a final view in the form of a report and a draft Bill.101

On 9 December 2021, the SALRC published its Issue Paper 39 on Project 148 on the domestication of the United Nations CRPD. On the strength of the responses received on the issue paper, the discussion paper is to be developed.102

3 Constitution

3.1 Does the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa contain provisions that directly address disability? If so, list the provisions and explain how each provision addresses disability.

Section 9 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 provides for equal protection and benefit of the law, and a right to non-discrimination to everyone. Section 9 provides for a vertically applicable right in section 9(3) in providing that the State may not unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language, and birth. Furthermore, section 9 provides for a horizontally applicable right to non-discrimination in section 9(4) when providing that no person may unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language, and birth. Sections 9(3) and 9(4) are the only sections which directly addresses disability in the Constitution.

In South Africa’s Initial Report on the implementation of the CRPD to the CRPD Committee, the government also reported on equality and disability.103 The SALRC in its December 2021 Issue Paper on the domestication of the CRPD, further provided an in-depth discussion pertaining to section 9 of the Constitution and disability.104

3.2 Does the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa contain provisions that indirectly address disability? If so, list the provisions and explain how each provision indirectly addresses disability.

The Constitution is the supreme law of the Republic of South Africa105 and is based on equality of outcomes. The Bill of Rights is contained in Chapter 2 of the Constitution and binds the State and private individuals.106 However, it should be noted that the rights contained in the Bill of Rights are not absolute and may be limited in terms of the limitation clause in the Bill of Rights.107 Though the Constitution as a whole is mostly concerned with state power and with the law, there are a number of provisions in the Bill of Rights that place, in certain circumstances, duties on private individuals.108 However, as most of the rights contained in the Bill of Rights apply to ‘everyone’ (or in some instances ‘every citizen’, ‘every child’, ‘every worker’, ‘every employer’, and ‘every trade union’), most of these rights would also be applicable to and include persons with disabilities. The majority of the rights contained in the Bill of Rights are therefore indirectly applicable to persons with disability. These rights are human dignity (section 10); the right to life (section 11); the right to freedom and security of the person (section 12); the right to freedom of trade, occupation and profession (section 22); labour relations rights (section 23); the right to health care, food, water and social security (section 27); the rights of the child (section 28); and the right to education (section 29). It should therefore be noted that the Constitution provides for the protection of disability as a substantive equality outcome.

4 Legislation

4.1 Does South Africa have legislation that directly addresses issues relating to disability? If so, list the legislation and explain how the legislation addresses disability.

South Africa does not have comprehensive disability legislation that deals exclusively with matters relating to disability or with persons with disabilities directly. In this regard see the discussions in questions 2.4 and 2.5 on the domestication of the CRPD.

The Employment Equity Act109 and the Promotion of Equality and the Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act (PEPUDA),110 make provision for reasonable accommodation for persons with disabilities. However, there is a need for the protection of persons with disabilities against discrimination and degradation through disability-specific legislation.

4.2 Does South Africa have legislation that indirectly addresses issues relating to disability? If so, list the main legislation and explain how the legislation relates to disability.

Apart from the Employment Equity Act111 and PEPUDA,112 which amongst others addresses issues pertaining to persons with disabilities, there are other laws that indirectly address issues relating to disability, namely:

- Accessibility113

Legislation pertaining to access to building, access to housing, a safe working environment, accessibility, equality, land transportation, and access to information:

- National Building Regulations and Building Standard Act 103 of 1977;

- Standards (SANS) PART S - Facilities for Persons with Disabilities;

- Housing Amendment Act 4 of 2001;

- Occupational Health and Safety Act 85 of 1993;

- Promotion of Equality and the Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act 4 of 2000;

- National Land Transport Transitional Act 5 of 2009;

- National Library of South Africa Act 2 of 1998; and

- South African Library for the Blind Act 91 of 1998.

- Protection against exploitation, violence and abuse and children’s access to justice and protecting children with disabilities from violence and abuse and ensuring their access to the justice system114

The rights of persons and children with disabilities are to be protected against exploitation, violence, and abuse and children’s access to justice are protected in sections 7, 9, 10, 12, and 28 of the Constitution. The following laws are relevant, however implementation of some of them might be lacking:

- Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act (SORMA) Act 13 of 2021;

- Older Persons Act 13 of 2006;

- Domestic Violence Act 116 of 1998;

- Children’s Act 38 of 2008; and

- Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977.

- Education115

The right to education is protected in section 29 of the Constitution and mentioned in various laws and policies:

- Integrated National Disability Strategy (INDS);

- Education White Paper 3: Transformation of the Higher Education System;

- National Plan for Higher Education;

- Education White Paper 6: Special Needs Education;

- 2012 Green Paper for Post School Education;

- South African White Paper on Post-school Education and Training; and

- Schools Act 84 of 1996.

- Health116

Issues surrounding mental health law and health law relating to autonomy, competency, and consent of persons with disabilities are:

- Sterilisation Act 44 of 1998;

- Mental Health Care Act 17 of 2002;

- National Health Act 61 of 2003; and

- Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act 1 of 2008.

Issues relating to the health rights of children with disabilities are touched upon in terms of section 28 of the Constitution and the National Health Act 61 of 2003.

- Labour practices117

The right to fair labour practices is protected in section 23 of the Constitution. Laws indirectly applicable to persons with disabilities are:

- Employment Equity Act 55 of 1998 and its Code of Good Practice: Key Aspects on the Employment of People with Disabilities;

- Technical Assistance Guidelines on the Employment of People with Disabilities (TAG);

- Labour Relations Act 66 of 1995, its Code of Good Practice on Dismissal;

- Basic Conditions of Employment Act 75 of 1997;

- Skills Development Act 97 of 1998;

- Skills Development Levies Act 9 of 1999; and

- Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act 130 of 1993.

- Adequate standard of living and social protection118

Sections 9 and 27 of the Constitution are applicable to persons with disabilities, and more particularly the intersection between disability and poverty which has an impact on the lives of persons with disabilities in South Africa. In this regard, the progressive realisation of the rights to access to social security and social assistance should be mentioned, together with the Social Assistance Act 13 of 2004.

- Political life119

The right to political life is protected in section 19 of the Constitution. The following legislation is applicable to the protection of persons with disabilities and their right to political life:

- Electoral Act 73 of 1998;

- Voter Registration Regulations 1998;

- Regulations on the Accreditation of Voter Education Providers of 1998;

- Regulations on the Accreditation of Observers of 1999; and

- Regulations Concerning the Submission of Lists of Candidates of 2004.

- Other legislation

Other laws that are applicable to persons with disabilities or might have an impact on persons with disabilities are:

- Skills Development Act 97 of 1998;

- Compensation for Injuries and Diseases Act 130 of 1993 (COIDA);

- Road Accident Fund Act 56 of 1996;

- Occupational Health and Safety Act 85 of 1993;

- Mine Health and Safety Act 29 of 1996;

- Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act 5 of 2000;

- Promotion of Access to Information Act 2 of 2000;

- National Education Policy Act 27 of 1996;

- Broad-based Black Economic Empowerment Act 53 of 2003; and

- National Sport and Recreation Act 110 of 1998.

5 Decisions of courts and tribunals

5.1 Have the courts (or tribunals) in South Africa ever decided on an issue(s) relating to disability? If so, list the cases and provide a summary for each of the cases with the facts, the decision(s), and the reasoning.

The South African courts place a strong emphasis on substantive equality to redress the inequalities of the past. In Harksen v Lane120 and Prinsloo v Van der Linde,121 the Constitutional Court indicated the place of substantive equality in South Africa by providing criteria to determine unfair discrimination. Essentially these criteria contain the reasonable accommodation necessary to give effect to the application of substantive equality or equality of outcomes for disadvantaged groups and individuals.

In this regard, the Constitutional Court determined in Prinsloo v Van der Linde122 that human dignity constitutes a criterion to determine unfair discrimination. The Court endorses the view that:

At the heart of the prohibition of unfair discrimination lies a recognition that the purpose of our new constitutional and democratic order is the establishment of a society in which all human beings will be accorded equal dignity and respect regardless of their membership of particular groups.123

Furthermore, PEPUDA124 provides for the establishment of Equality Courts in all magisterial districts, which in principle should provide easy access to persons who believe they have been discriminated against on, amongst others, the basis of disability. It is important to note that the onus is on the alleged discriminator to prove in the Equality Courts that the discrimination did not take place. The importance of human dignity was also emphasised in WH Bosch v The Minister of Safety and Security & Minister of Public Works125 when the Equality Court in Port Elizabeth held that:

There is no price that can be attached to dignity or a threat to that dignity. There is no justification for the violation or potential violation of the disabled person’s right to equality and maintenance of his dignity that was tendered or averred by the respondent. The court therefore found the discrimination to have been unfair.

The Bosch-judgment in 2005 directed that all South African Police Services (SAPS) stations be made accessible for persons with disabilities. In another Equality Court case in Germiston, Esthe Muller v Minister of Justice and Minister of Public Works,126 an out-of-court settlement of 2004 created precedence by directing that all court buildings be made accessible. Both the judgments (Bosch and Muller) resulted in the creation of a dedicated programme within the Department of Public Works to renovate existing public services buildings.

Similarly, the Equality Court ruled in favour of Lettie Oortman against the St Thomas Aquinas private school when it directed that not only was the school obliged to re-admit Chelsea Oortman, but that the school had to ‘take reasonable steps to remove all obstacles to enable Chelsea to have access to all the classrooms and the toilet allocated to her by using a wheelchair’. The South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC)127 assisted Oortman and addressed the issues relating to the rights of persons with disabilities in the Mpumalanga Equality Court judgment of Lettie Hazel Oortman/St Thomas Aquinas Private School and Bernard Langton.128 In this case, the Equality Court dealt with the question of whether the school had unfairly discriminated on the prohibited ground of disability, against one of their learners. The court found that the school had not taken all the reasonable steps to accommodate her and did not remove all the obstacles for the learner in order to enable her to have access to the classroom, washbasin, and toilet allocated to the learner by using her wheelchair.129

In Standard Bank Ltd v CCMA,130 the Bank employee was dismissed after being injured in a car accident. The Bank failed to accommodate the employee, which renders dismissal ‘automatically unfair’.131 The Bank had not complied with the Code of Good Practice on Dismissal. The court noted that the underlying constitutional rights are the right to equality, the right to human dignity, the right to choose an occupation, and the right to a fair labour practice. Justice Pillay noted that the marginalisation of persons with disabilities in a workplace is not because of their ability to work, but because the disability is seen as an abnormality or flaw; that integration and inclusion in mainstream society aim not only to achieve equality but also to restore the dignity of persons with disabilities.132 In Smith v Kit Kat Group (Pty) Ltd,133 the employee alleged that he was unfairly discriminated against when the employer refused to allow him to resume his duties for ‘cosmetically unacceptable’ reasons. The employee attempted suicide, which resulted in the disfigurement to his face, as well as impaired speech. The court found that the employer could not rely on cosmetic reasons for the dismissal as he did not occupy a role such as a fashion model. Furthermore, the court observed that the speech impediment was not so severe that the employee would not be able to perform his duties and the view of the court was that minimal accommodation by the employer was required. Furthermore, it is important to note that the employer did not investigate to determine the extent of the impairment, nor did the employer consider whether the employee could be accommodated in another role. This means that the Code of Good Practice on Dismissal was not consulted in this regard.

In Makana People’s Centre v Minister of Health,134 the Constitutional Court did not confirm the Gauteng High Court’s decision which declared sections of the Mental Health Act,135 that allow for the involuntary detention of mental health patients, as unconstitutional. Makana People’s Centre approached the court in the aftermath of the Life Esidimeni tragedy, where 100 mental health patients died after being moved to incapacitated non-government organisations (NGOs). It was argued that sections 33 and 34 of the Mental Health Act136 were unconstitutional and invalid, as they did not provide for automatic independent review before or immediately after the involuntary detention of a mental health patient. However, the Constitutional Court held that sections 33 and 34 included steps that involved senior health officials and legal practitioners who were all tasked to ensure the involuntary treatment of a patient was fair and warranted.

6 Policies and programmes

6.1 Does South Africa have policies or programmes that directly address disability? If so, list each policy and explain how the policy addresses disability.

South Africa’s Initial Report to the CRPD Committee identifies a variety of policies,137 and how the policies address disability. The SALRC, in its issue paper, identified further policies which are:138

- National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2013-2020;

- Disability Framework for Local Government 2015-2020;

- Technical Assistance Guidelines on the Employment of People with Disabilities;

- Framework and Strategy for Disability and Rehabilitation Services in RSA 2015-2020;

- Policy Guidelines for the Licensing of Residential Facilities and/or Day Care Facilities for Persons with Mental Illness and/or Severe or Profound Intellectual Disabilities; and

- Standardisation of Assistive Devices in South Africa: A Guideline for Use in the Public Sector and the National Rehabilitation Policy 2006.

6.2 Does South Africa have policies and programmes that indirectly address disability? If so, list each policy and describe how the policy indirectly addresses disability.

South Africa reported in its Initial Report139 to the CRPD Committee that apart from the Constitution and PEPUDA various measures have been taken to promote the establishment of a society in which all human beings are guaranteed legal protection against discrimination. Persons with disabilities have been included as a designated group in all affirmative action policies and programmes to redress past discrimination. The Departments of Health, Basic Education, as well as Justice and Constitutional Development, have developed braille public awareness and education materials on key legislation and policies as well as disability services related to, amongst others, the Children’s Act,140 the Domestic Violence Act,141 and the Maintenance Act.

7 Disability bodies

7.1 Other than the ordinary courts or tribunals, does South Africa have any official body that specifically addresses violations of the rights of persons with disabilities? If so, describe the body, its functions, and its powers.

There are no other bodies other than courts that specifically address the violation of the rights of persons with disabilities.

7.2 Other than the ordinary courts or tribunals, does South Africa have any official body that, though not established to specifically address the violation of the rights of persons with disabilities, can nonetheless do so? If so, describe the body, its functions, and its powers.

The only other bodies addressing the violation of the rights of persons with disabilities are the National Human Rights Institutions discussed in question 8 below.

8 National human rights institutions, Human Rights Commission, Ombudsman or Public Protector

8.1 Do you have a Human Rights Commission or an Ombudsman or Public Protector in South Africa? If so, does its remit include the promotion and protection of the rights of persons with disabilities? If your answer is yes, also indicate whether the Human Rights Commission or the Ombudsman or Public Protector of South Africa has ever addressed issues relating to the rights of persons with disabilities.

South Africa has a South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC)142 which has a constitutional mandate (sections 181 and 184 of the Constitution) as an independent body to promote, protect, and monitor the rights of all South Africans. It is, however, acknowledged that capacity challenges within the commission cause significant delays in the effective investigation and finalisation of complaints.143 The SAHRC is required by the Constitution and PEPUDA to report on, amongst others, the state of equality in the country. The inaugural Equality Report of the SAHRC released in 2012 included two chapters on disability.144 The first chapter focused on the types of barriers experienced by persons with disabilities which detract from their standing as equal citizens. The second chapter on disability presented quantitative outcomes of a research project conducted to determine the equality challenges experienced by youth with disabilities compared to their able-bodied peers. The study found substantive inequality in outcomes between young persons with disabilities and their able-bodied peers in education, employment, and livelihoods.145

In the SAHRC ‘Towards a Barrier-free Society Report’ published in 2002 a number of recommendations were made. It was noted that legislation governing the accessibility of built environments should focus on improving the preconditions for equal participation and dignity and providing mechanisms for governance, administration, and enforcement. It also recommended an urgent review of the South African legislative framework for accessibility and the built environment in order to reflect constitutional rights; ensure safe, healthy and convenient use for all, and include international standards for universal access.146 The SAHRC conducted a number of investigations into allegations of human rights violations in mental health facilities over the past few years and has made recommendations in respect of both prevention of recurrence, as well as improvement of conditions in general. Furthermore, the SAHRC monitors the implementation of these recommendations.147

The SAHRC’s constitutional mandate (established in terms of sections 181 and 184 of the Constitution) includes the promotion and protection of the rights of groups which are vulnerable to discrimination, exclusion, and inequality. The SAHRC, as an ‘A’ status national human rights institution and in line with its constitutional mandate, has the potential to be part of the framework as an independent mechanism to promote, protect, and monitor the implementation of the CRPD. In this regard, the South African government reported to embark on a formal consultative process, which will include civil society, in establishing this monitoring framework as required by article 33(2) of the CRPD.148

It must be noted that the CRPD Committee in its Concluding Observations noted that the SAHRC should be empowered as the national independent monitoring mechanism to monitor all institutions and settings in which persons with disabilities are deprived of their rights.149 The CRPD Committee further recommended that the designation of the SAHRC as an independent monitoring mechanism be expedited. In this regard, the CRPD Committee recommended that sufficient financial resources be allocated to enable the SAHRC to execute its mandate fully.150

9 Disabled peoples organisations (DPOs) and other civil society organisations

9.1 Does South Africa have organisations that represent and advocate for the rights and welfare of persons with disabilities? If so, list each organisation and describe its activities.

There is a wide range of advocacy and self-help organisations, which includes organisations such as Disabled People South Africa (DPSA), the National Council of and for Persons with Disabilities (NCPD), and Champion of Hope. Single-issue national organisations such as the South African Federation for Mental Health (SAFMH) and Down Syndrome South Africa, to name just a few. There are mainly three different types of disability organisations (DPOs) in South Africa. They are:151

- Cross-disability organisations such as NCPD and Champion of Hope, which represent the interests of all persons with disabilities in South Africa.

- Diagnostic-focused organisations which represent a medical diagnostic group such as SAFMH and Down Syndrome South Africa. These DPOs are provincial organisations that assist their members in a particular province, for example Down Syndrome Association of the Western Cape (DPSAWC).

- Population-specific organisations, represent a population group such as children with disabilities, for example, The Sunshine Association.

9.2 In the countries in your region, are DPOs organised/coordinated at a national and/or regional level?

See question 9.1 above. The South African government reported in its Initial Report to the CRPD Committee that they recognise the right of persons with disabilities to be represented through organisations of persons with disabilities, as well as parents’ organisations, rather than through organisations for persons with disabilities. Financial support from government to organisations for and of persons with disabilities at national and provincial levels is predominantly through subsidisation by the Departments of Social Development, Health, and Labour, with a strong bias at this stage towards organisations for persons with disabilities, rather than organisations of persons with disabilities. Organisations of persons with disabilities at local level currently receive virtually no direct financial support from government but have access to funds through the National Development Agency (funded by the Department of Social Development), as well as the National Lottery Distribution Trust Fund which distributed a total of USD 65.2 million between 2008 and 2011 to organisations of and for persons with disabilities. The government further reported that there is an urgent need to finalise a framework for the creation of an enabling environment for organisations of persons with disabilities to strengthen their capacity to advocate, empower, and monitor the rights of persons with disabilities more effectively. 152

9.3 If South Africa has ratified the CRPD, how has it ensured the involvement of DPOs in the implementation process?

South Africa, in the drafting process of its first Initial Report to the CRPD Committee, involved organisations of and for persons with disabilities, including the South African Disability Alliance (SADA). SADA comprises of representatives from 13 national affiliated organisations of and for persons with disabilities.153 Verbal and oral submissions by DPOs to the Parliamentary Committee on Women, Children and People with Disabilities were considered. The draft report was released for public comment on 12 November 2012 and was also emailed to stakeholders amongst other, organisations of and for persons with disabilities at national, provincial, and local levels, and submissions from civil society including submissions from national organisations of and for persons with disabilities were received.154 In this regard, the South African government acknowledged the valuable contributions made by these organisations and recognised the role that the disability sector and these organisation in particular, continues to play in promoting and adopting a right-bases approach for persons with disabilities and their families. However, the Initial Report acknowledges the capacity and resource constraints that limited the extent to which DPOs and disability service organisations were able to participate in the development of the report. In this regard, the Initial Report, in particular, refer to the voices of persons with disabilities living in rural areas, in residential and/or institutional care, persons with psychosocial disabilities, as well as children with disabilities.155

Furthermore, the SALRC invited DPOs to submit written comments, representations, or requests to the Commission’s Issue Paper on the domestication of the CRPD during 2021. 156

9.4 What types of actions have DPOs themselves taken to ensure that they are fully embedded in the process of implementation?

9.5 What, if any, are the barriers DPOs have faced in engaging with implementation?

Funds remain the greatest challenge to the activities of DPOs.

9.6 Are there specific instances that provide ‘best-practice models’ for ensuring the proper involvement of DPOs?

It is difficult to ascertain at this stage if ‘best-practice models’ for ensuring proper involvement of DPOs are in place. However, the South African government recognises the role that the disability sector, and DPOs in particular, continue to play in promoting and adopting a rights-based approach for persons with disabilities and their families during the drafting process of its Initial Report to the CRPD Committee.157 Furthermore, as seen from question 9.3 above, the SALRC invited all stakeholders, including DPOs to submit written comments, representations, or requests to the Commission’s Issue Paper on the domestication of the CRPD. Similarly, the SALRC will invite all stakeholders, including DPOs to submit written comments, representations, or requests to the Commission’s Discussion Paper during the public participation process.

9.7 Are there any specific outcomes regarding successful implementation and/or improved recognition of the rights of persons with disabilities that resulted from the engagement of DPOs in the implementation process?

9.8 Has your research shown areas for capacity building and support (particularly in relation to research) for DPOs with respect to their engagement with the implementation process?

9.9 Are there recommendations that come out of your research as to how DPOs might be more comprehensively empowered to take a leading role in the implementation processes of international or regional instruments?

See questions 9.2, 9.3, and 9.6 above. The DPOs must actively engage when the SALRC invites DPOs to submit written comments, representations, or requests to the Commission’s Issue Paper and Discussion Paper on the domestication of the CRPD. Furthermore, DPOs should actively participate in South Africa’s second, third, and fourth periodic reports which were due by 3 June 2022. These reports have not been finalised at the time of writing this country report.

9.10 Are there specific research institutes in South Africa that work on the rights of persons with disabilities and that have facilitated the involvement of DPOs in the process, including in research?

See questions 9.2, 9.3 and 9.6 above. There are currently no specific research institutes in South Africa that work on the rights of persons with disabilities, which have facilitated the involvement of DPOs in the process. However, it is noted that the SALRC invites DPOs to submit written comments, representations, or requests to the Commission on the domestication of the CRPD. 158

10 Government departments

10.1 Do you have a government department or departments that is/are specifically responsible for promoting and protecting the rights and welfare of persons with disabilities? If so, describe the activities of the department(s).

The South African government established the Disability Programme within the former Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) in the Presidency in 1995, which evolved into the Office on the Status of Disabled Persons (OSDP) in the Presidency in 1997, and finally evolved into the Department of Women, Children and People with Disabilities (DWCPD) in May 2009. The DWCPD incorporated the former OSDP and is responsible for driving government’s equity, equality, and empowerment agenda in terms of those living with disabilities. The South African government reported in its Initial Report to the CRPD Committee that the DWCPD is ready to introduce systems into the planning, monitoring, and evaluation system to fast-track systematic implementation of the CRPD across all three spheres of Government (national, provincial, and local spheres) through better monitoring, support, and coordination.159 It must be noted that government reported that the establishment of the DWCPD, had the unintended consequence of slowing down the transformation agenda in the short term due to the time taken in establishing an administration in the Department. Furthermore, resourcing constraints were reported within the DWCPD.160 However, the DWCPD is working towards consolidating awareness-raising efforts into a targeted, integrated, and branded programme. South Africa reported that government will be dealing with this aspect in their next periodic report to the CRPD Committee.161

11 Main human rights concerns of people with disabilities in South Africa

11.1 Contemporary challenges of persons with disabilities in South Africa (eg in some parts of Africa is ritual killing of certain classes of PWDs such as persons with albinism occurs).

The South African government in its Initial Report to the CRPD Committee reported in detail on the contemporary challenges faced with the implementation of the specific CRPD articles.162 In this regard, the CRPD Committee in its Concluding Observation, also expressed concerns regarding these challenges and made several recommendations.163 However, of particular concern is the acknowledgement in the Initial Report that persons with disabilities in general, but particularly those from poor and/or rural communities, as shown in the numerous testimonies, are still exposed to inhumane, degrading, and cruel treatment by people, services, and systems due to the persistent attitudinal, physical, and communication barriers existing in society.164

11.2 Describe the contemporary challenges of persons with disabilities, and the legal responses thereto, and assess the adequacy of these responses to:

It should be noted that South Africa in its first Initial Report to the CRPD Committee reported on challenges, and its legal responses thereto. Further, the CRPD Committee in its Concluding Observations assessed and responded to these challenges through recommendations. These challenges recorded were:

Access and accommodation: See question 5.1 above, and paragraphs C.69 to C.115 of South Africa’s Initial Report under article 35 of the Convention to the CRPD Committee regarding article 9 of the CRPD and accessibility reporting on the physical environment, information and communication technology (ICT), and transport. In this regard also consult paragraphs N.177 to N.182 on personal mobility and Q.191 to Q.197 on respect for home and the family.165

Access to social security: See paragraphs C.69 to C.115 of South Africa’s Initial Report under article 35 of the Convention to the CRPD Committee regarding article 9 of the CRPD and accessibility, as well as paragraphs V.317 to V.319 on article 28 of the CRPD, adequate standard of living and social protection.166

Access to public buildings: See question 5.1 above and paragraphs C.69 to C.115 of South Africa’s Initial Report under article 35 of the Convention to the CRPD Committee regarding article 9 of the CRPD reporting on the physical environment.167

The CRPD Committee in its Concluding Observations to the Initial Report of South Africa made recommendations on accessibility, and in particular to step up measures to enforce the National Building Regulations and Building Standards Act,168 and to monitor progress and reinforce sanctions for lack of compliance with accessibility standards in public and private sector buildings. 169

Access to public transport: See paragraphs C.69 to C.115 of South Africa’s Initial Report under article 35 of the Convention to the CRPD Committee regarding article 9 of the CRPD on accessibility and reporting on accessible transport.170

The CRPD Committee in its Concluding Observations to the Initial Report of South Africa noted with concern the absence of a clear national strategy on accessibility and public transport in rural areas. 171

Access to education: See paragraphs C.69 to C.115 of South Africa’s Initial Report under article 35 of the Convention to the CRPD Committee regarding article 9 of the CRPD and accessibility, as well as paragraphs R.198 to R.260 on article 24 of the CRPD and education.172

The CRPD Committee in its Concluding Observations to the Initial Report of South Africa made recommendations to adopt, implement, and oversee inclusive education as the guiding principle of the education system and develop a comprehensive plan to extend it nationally. The CRPD Committee also recommended that efforts should be intensified to allocate sufficient financial and human resources for reasonable accommodations that will enable children with disabilities, to receive inclusive and quality education. Further, the CRPD Committee recommended that South Africa establish an effective and permanent programme for training teachers in inclusive education, including learning sign language, Braille, and Easy Read skills.173

Access to vocational training: See paragraphs C.69 to C.115 of South Africa’s Initial Report under article 35 of the Convention to the CRPD Committee regarding Article 9 of the CRPD and accessibility, as well as paragraphs R.198 to R.260 on article 24 of the CRPD and education, and paragraphs U.306 to U.313 on article 27 of the CRPD, work and employment.174

Access to employment: See paragraphs C.69 to C.115 of South Africa’s Initial Report under article 35 of the Convention to the CRPD Committee regarding article 9 of the CRPD and accessibility, as well as paragraphs U.288 to U.313 on article 27 of the CRPD, work and employment.175

The CRPD Committee in its Concluding Observations to the Initial Report of South Africa recommended that government adopt a strategy to increase productive and decent work and the employment of persons with disabilities in the public and private sectors, including through mechanisms to ensure that reasonable accommodations are provided, and to prevent discrimination against persons with disabilities and their families in the labour market. Furthermore, the CRPD Committee recommended that effective measures are adopted for making the physical environment of workplaces accessible and adapted for persons with disabilities, including reasonable accommodation, especially for persons with motor impairments, and provide training to employers at all levels on respect for the concept of reasonable accommodation.176

Access to recreation and sport: See paragraphs C.69 to C.115 of South Africa’s Initial Report under article 35 of the Convention to the CRPD Committee regarding article 9 of the CRPD and accessibility, as well as paragraphs X.346 to X.368 on article 30 of the CRPD and participation in recreation and sport.177

The CRPD Committee in its Concluding Observations to the Initial Report of South Africa made recommendations that government expedite action to complete the process of revising the Copyright Act178 and ratifying the Marrakesh Treaty.179

Access to justice: See paragraphs C.69 to C.115, as well as G.126 to G.135 of South Africa’s Initial Report under article 35 of the Convention to the CRPD Committee regarding article 9 of the CRPD on accessibility and access to justice.180

The CRPD Committee in its Concluding Observations to the Initial Report of South Africa made recommendations to adopt measures to ensure that all persons with disabilities have access to justice, and information and communication in accessible formats, such as Braille, tactile, Easy Read, and sign language. The CRPD Committee further recommended that government must ensure a systematic training programme for judicial and law enforcement officials, including police and prison officials, on the right of all persons with disabilities to justice, including involving persons with disabilities as judicial officials. 181

11.3 Do persons with disabilities have a right to participate in political life (political representation and leadership) in South Africa?

Section 19 of the Constitution guarantees the right of all citizens to make political choices, form political parties, participate in the activities of political parties, vote in elections for any legislative body established in terms of the Constitution, and to do so in secret, and to stand for public office and, if elected, to hold office.

The South African government reported in detail in South Africa’s Initial Report under article 35 of the Convention to the CRPD Committee and more particularly paragraph W.330 on article 29 of the CRPD and participation in political and public life. This included the right to vote and holding public office.182

11.4 Are persons with disabilities’ socio-economic rights, including the right to health, education and other social services protected and realised in South Africa?

South Africa in its Initial Report under article 35 of the Convention to the CRPD Committee, reported that priority areas for implementation of the CRPD for the period 2009 to 2014 were incorporated into the national priorities of government which, amongst others, included education, employment, health, safety and security, as well as, to a lesser extent, rural development.183 Furthermore, South Africa reported in detail on the implementation of health, education, and social services protected and realised in South Africa.184

11.5 Specific categories experiencing particular issues/vulnerabilities:

South Africa’s Initial Report under article 35 of the Convention to the CRPD Committee reported extensively on women with disabilities, protected under article 6 of the Convention. The government confirmed that South Africa remains committed to the attainment of gender equity and equality as it pertains to women and girls with disabilities and as illustrated in the country’s extensive legislative and policy framework. South Africa ratified the CEDAW, as well as the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development. However, the government acknowledges that a major concern with regard to disability and gender is the persistent violence against and victimisation of women and children, in particular women and girls with disabilities. Women with disabilities are represented on the Commission on Gender Equality (CGE), established in terms of Chapter 9 of the Constitution. The CGE has a mandate to evaluate government policies, promote public education on gender issues, make recommendations to government for law reform, investigate complaints, and monitor government’s compliance with international conventions. Women with disabilities are further affirmed through a range of targeted programmes and events by several government departments. However, government recognised that improved coordination and targeting of these efforts will significantly strengthen impact. 185

South Africa’s Initial Report under article 35 of the Convention to the CRPD Committee reported extensively on children with disabilities. Apart from the constitutional protection of children in section 28 of the Constitution, the government reported that ‘a child’s best interests are of paramount importance in every matter concerning the child’.186 The rights of a child underlie all decision making with regard to legislation, policies, and programmes in South Africa. The Children’s Act187 further mandates the State to respect, promote, and fulfil the child’s rights set out in the Bill of Rights, contained in Chapter 2 of the Constitution. Government also reported that a national strategy for the integration of services to children with disabilities has been developed in consultation with approximately 2 500 stakeholders from national and provincial Departments of Social Development, other key government departments and institutions, as well as stakeholders in the parents, children, and disability sectors.188

12 Future perspective

12.1 Are there any specific measures with regard to persons with disabilities being debated or considered in South Africa at the moment?

12.2 What legal reforms are being raised? Which legal reforms would you like to see in South Africa? Why?